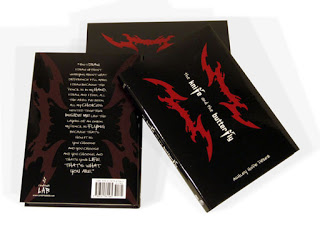

Welcome to our humble stop on the blog tour for Ashley Hope Pérez’s latest novel, The Knife and the Butterfly, out now from Carolrhoda Books. We posted an in-depth review on Monday and on Wednesday a follow-up chat on the overarching ideas Ashley is covering during her blog tour. Today we’ve got some thoughts from the author herself on what it means to write a book with an edge–and what it doesn’t mean.

A brief bio to begin: Ashley Hope Pérez is the author of two young adult novels, WHAT CAN’T WAIT and THE KNIFE AND THE BUTTERFLY. She also is a passionate teacher and student working on her PhD in comparative literature. At the moment, she lives in Paris with her husband and son where they enjoy culture, croissants, and cramped living quarters.

With no further ado, here’s Ashley:

The term “edgy” is flying around in talk about The Knife and the Butterfly and the voice in which it’s told. And trust me, I’m thrilled that I (cautious rule-follower to the max in all other areas) have pulled off writing in the voice of a 15-year-old boy who happens to be homeless, in trouble with the law, and caught up in a gang.

What’s the one thing that would make me happier? If I could give “edgy” the particular edge it has for me.

![]() The thing is, the edge that interests me most has little to do with sex or gangs or profanity. These are, in my view, simply accidents of my characters’ world (think: inner-city, no safety nets). Sometimes when I’m talking about this aspect of The Knife and the Butterfly, I feel like a woman giving a tour of a house she’s renting: “I know, I know, I wish the wallpaper in here were nicer, but this is what I’ve got to work with.”

The thing is, the edge that interests me most has little to do with sex or gangs or profanity. These are, in my view, simply accidents of my characters’ world (think: inner-city, no safety nets). Sometimes when I’m talking about this aspect of The Knife and the Butterfly, I feel like a woman giving a tour of a house she’s renting: “I know, I know, I wish the wallpaper in here were nicer, but this is what I’ve got to work with.”

The world of The Knife and the Butterfly is, indeed, a world on loan. It’s borrowed from the news (the gang fight that opens the novel was inspired by an actual event in Houston). It’s borrowed from the alleys and taquerías and run-down parks that I scoped out while writing. It’s borrowed from interviews with Houston teens and MS-13 members that I read.

Now, this is where I could say, “the book has to be rough because the world it’s about is rough.” There’s plenty of truth to that, but it’s not the truth I want to take up right now. And my novel, like all fiction, is far from a facsimile of the actual world. The cussing is scaled WAY back from reality (for a teen like Azael), and most of the violence and sexual stuff in The Knife and the Butterfly is thematic, not explicit or graphic.

What if we think about the “edge” in a new way? What if it’s not so much about the themes and material in the book but rather about how that book and a real reader relate?

Here’s the edge that really matters in YA (and in all fiction): the way something a book can take the reader by surprise, almost violently. Not in a “I can’t believe the butler did it” way, but in a “nothing could have prepared me for how X would affect me” way.

In that previous sentence, X stands for the edge. It might be the beauty of language (or its deliberate plainness), a character, or even a turn in the plot. The important thing is that a truly edgy book doesn’t leave us intact; it makes us vulnerable to something—an emotion, a thought, a realization, a fear, a discovery, a way of seeing—and it forces us to reckon with it. Certainly this edge is different for different readers, even when they are reading the same book, but we all need it to evolve our reading lives.

I doubt that I need to remind anyone of the whole debate sparked by Meghan Cox Gurdon’s Wall Street Journal article, “Darkness Too Visible.” (If you have no idea what I’m talking about or want to know my take, look at this or this.) The only thing that I want to bring back from that piece was the longing—false nostalgia, even—for safety in books. As a parent, I understand this feeling. Really, I do. But I am more than just a parent. I am a reader, a writer, and a student of literature, and in those roles, I have come to believe that safe books are inert books, dead books.

If we feel 100% safe with what we’re reading, if we meticulously avoid the chance of encountering the edge, we’re very unlikely to be deeply affected by our reading. There has to be an element of risk and exposure in the reading relationship if anything very profound is going to occur. A great book is not a safe place for the reader.

Don’t misunderstand me. An edgy book needn’t be dark or peppered with profanity. But there must be something about the book that takes the reader to a place she could not have said, in advance, that she wanted to go.

That something is the edge I hope readers will find in my writing. The rest… it’s just wallpaper.

Thanks so much, Ashley, for stopping by and sharing your writerly thoughts! And, for readers of this post, you can visit Ashley’s blog, follow her on twitter @ashleyhopeperez, or find her on facebook.

Watch for more insights into the writing of the novel throughout Ashley’s The Knife and the Butterfly blog tour. See the full tour schedule here.

You can buy The Knife and the Butterfly from your favorite local bookseller or order it online.

I agree that our best literature is not "safe." And yet, the beauty of a book is that it is safe in another sense–reading about an experience is not exactly the same as living it. Reading about a drug addict is not the same thing as becoming a drug addict, for example.

So I suppose what I mean, and how I relate it to this post, is that books are *physically* safe–we can read about any experience while sitting in a chair at home. But edgy books are not *emotionally* safe; they ask us to take emotional risks and make emotional investments.

I don't object to people who don't like edgy books seeking out books they think are emotionally safer. To each her own, and they can read what they want. I only object when they want to take the edgy books away from the rest of us.

When I started grad school, people said things like, "if it doesn't make you bleed, it's a waste of time," and "if it doesn't make someone uncomfortable, you're speaking into the void." I got impatient with that kind of idea, it seemed like people were advocating Annoying Others for annoyances' sake, and I didn't like that. Why couldn't everyone just get along???

Years down the road, I'm beginning to see something in publishing – it's a chock-full field. Young adult and children's lit is stuffed with talented and entertaining people, and I've learned that even if your work really matters, it may matter only to you. And if your work speaks… well, it's unacceptable if my work speaks only to me.

Somewhere out there is a kid who doesn't need a hundred thousand other pretty, soft-focus boy-meets-girl-and-then storylines, s/he needs THIS story. And so, edgy or not, THIS is the story I need to tell…

That's how I relate to the "edgy." Like the author, I feel it's not in specific things like language or behavior – that's fairly external. Jen, I agree: emotional vulnerability is a lot edgier than dropping the f-bomb every four words. That's more of where I think I want to be – on the emotional edge, telling stories that are about taking risks, and remembering how to do that.

Brilliant, brilliant, ladies! Thank you for giving me the chance to continue thinking through my idea.

Jennifer, I agree that risking emotional safety is what's really at stake–and in a good way. Like you, I understand the many reasons why people might not want to take this risk (or might not want their kids to), but I maintain that they are missing out on something critical that makes literature literature.

Tanita, I think I am going to make the following quotation from your comment my mission statement as a writer: "there is a kid who doesn't need a hundred thousand other pretty, soft-focus boy-meets-girl-and-then storylines, s/he needs THIS story. And so, edgy or not, THIS is the story I need to tell…"

Thank you both.

I agree with everything that's been said here. I think any writer who is worth his or her salt will realize that writing in general is not "safe." You open yourself up to criticism, misinterpretation, etc. A good story bleeds through you like ink on a page. In my program, one of the graduating students read an excerpt from her creative thesis. Judging by the passion and power of her work, we all bled and were all changed in that moment. That's what a good story does.

Thank you, Lin. The moment you described is precisely what I'm talking about. It's nothing that we can prepare for; it's something that happens to us and changes us before we know what's going on. Thanks so much for weighing in.