Cross-posted at Fiction, Instead of Lies, and kind of a continuation of the response/discussion to the comments on this blog post.

Cross-posted at Fiction, Instead of Lies, and kind of a continuation of the response/discussion to the comments on this blog post.

Imagine two best friends, united against a common enemy. It is the pitch of midnight, and they are making a desperate flight across country, to deliver a package necessary to the scrappy resistance fighters desperately battling a corrupt government for their freedom. There’s been a car accident, so they’re the emergency fill-ins. Neither of them are supposed to be where they are. And then there’s another, bigger accident. In a foreign country, neither with any business being there, the girls have to split up and vanish — and those who are caught disappear into the night and fog — for good.

It is the pitch of midnight. And the enemies of truth and right are playing for keeps.

Wouldn’t you be on the edge of your seat reading this book? I know I was…at times feeling quite hopeless and desolate upwellings of terror and the word, “Nooooooo!” pulled from deep within. I could imagine myself there — and making a horrible mess out of all of it. If you read it, you’d imagine yourself there, too.

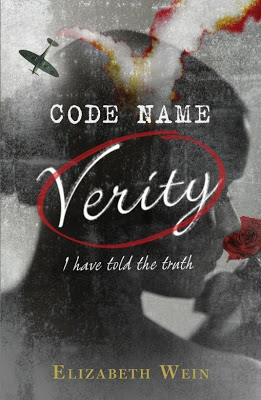

It’s exciting. There’s espionage, airplanes, parachutes, firefights, and girls hunched in dark places under umbrellas, waiting for safety in breathless silence. There’s fear — bleak terror — great laughs, and the best friends you could ask for.

So, why’d we want to go and ruin it all by calling it historical fiction???

For a long time, one of the biggest concern of the Gatekeepers in our world o’ books was where to put historical fiction in the canon for young people. Was it “edutainment?” Was it fictionalizing history or historicizing fiction, sliding in a character’s fears and hopes and their thoughts where students perhaps ought to be better employed with learning dates and facts? Was it, and could it ever be, authentic?

These big questions were hashed out in historical journals and literary papers and I think it’s safe to say that though some historians remained uncomfortable, the majority of teachers, especially in the middle grades and junior high, where I served most of my time, felt that historical fiction was an important lamp to illuminate some darker corners. Especially with the rise of multiculturalism, some pieces of history that “we” – as in mainstream, dominant culture America – had not realized were part of “our” story needed to be dug out, rediscovered, and explored. Historical fiction was a great tool to bridge the gap with the unknown pasts of a commingled people with the commonality of the human story. Through the insertion of tiny, literal accuracies, historical fiction maintains a sturdy cover story of “true enough,” and more quickly engages young minds with the history before them. For most students, blending stories into a study of history helps to recreate the past as a dynamic place.

For other students — and for many of the rest of us — it’s an automatic “No.” Seriously. Go back and read the comments of the people who have talked about CODE NAME VERITY. “I don’t usually read war books…” “I’m not usually a fan of wartime historical fiction…” “I don’t normally do historical fiction…” Is it the war? Or is it just the past?

Author and teacher Ashley Hope Pérez responded to a post a few days ago, “I have a kind of knee-jerk recoil from the term “historical fiction,” probably because I know how it would make my kiddos eyes glaze before they even tasted the prose.” Jen over at Reading Rants agrees: “In my experience, most teens won’t even look at hist. fic. unless they have to read it for a school assignment. You know, stuff like My Brother Sam is SO Dead, or Johnny TREmain (as in TREmendously booorrrriiinnggg!).”

It’s baffling, really — no one characterizes, say, The Great Gatsby as historical fiction — or, a better example, The Key to Rebecca, not really. They’re listed as what they are, first – a novel of manners. An espionage thriller. Nothing to do with their setting and time period and everything to do with their plot content. In part, the sticky label of “historical fiction” is a marketing key for parents and librarians to identify the book: Here is something semi-educational to slap into the unsuspecting hands of innocent youth. Go to it!

That, mainly, explains why it doesn’t work.

Oh, come on: how many of us pick up a book of fiction for the its educational aspects? Not me! When I pick up a book, I want a good story, period. Unfortunate, but the label attached to this genre can sometimes shoot even a very good book in the foot. The only thing we can really do about that is to book talk, book talk, book talk. Word of mouth will win the day! Talk up the other aspects of the story – the plot, the characterizations, the types of planes, the outfits, the guns. You can order the story bits by their importance: CODE NAME VERITY is a.) a thriller, b.) a story of the kind of friendships that start in a bomb shelter c.) a fast-paced, dangerous tale full of espionage, spies, and double agents d.) a cracking good read, which just happens to be, e.) set about sixty-some years ago.

I think we can just leave off that last one.

As an author, I can say that one of the hardest things about writing historical fiction is the tightrope walk the author has to do — between historical accuracy and humanity. It’s important not to infodump dates and names, but it’s also crucial not to veer the characters – and the details of their daily lives – into obvious anachronisms by using more modern tools, language, and attitudes about social tolerance which make the historical accuracy a lie. Further, I know that writing about a war is tough because historical accuracy is a must – the dates have to match up, including when historical people die, and when troops moved in fact, they must move in fiction, too. But people’s characters — their loves and needs and fears and even their grocery lists — are much the same, no matter what era they’re in. Sure, they might swear a bit less or a bit more, wear their hair down, their pant-legs shorter; they might speak another language, but the human animal remains a constant – an important thing to know.

As a (former, now) teacher, I know that this is the saving grace of historical fiction, or any fiction, really — the people. The characters make the story, and you just have to close your eyes to the fact that since it’s history, you think you already know how it’s going to end, jump in to knowing the characters, and let go —

As a (former, now) teacher, I know that this is the saving grace of historical fiction, or any fiction, really — the people. The characters make the story, and you just have to close your eyes to the fact that since it’s history, you think you already know how it’s going to end, jump in to knowing the characters, and let go —

— you may find yourself on the edge of your seat, in the pitch of midnight, with two best friends, delivering a necessary package, having an accident, and disappearing into the night and fog…

Call it “historical fiction” or “historical suspense” or anything you’d like, the word is out: CODE NAME VERITY is a sensational novel. Don’t forget to check out the other stops along the way for the blog tour.

* Chachic’s buzzing about Verity; stop by and read her great review, as well as some discussion on starting an All Spoilers, All the Time discussion group so that people don’t have to keep the spy secrets to themselves.

* The Scottish Bookstrust is a fab organization interesting young people in books. Visit them at BookTrust.org.uk for more from Elizabeth Wein about friendship in CODE NAME VERITY. And stay tuned for Monday’s review of the novel, and links to Elizabeth’s interview on the BBC’s Book Cafe!

Well, I wouldn't call The Great Gatsby historical fiction because it's not. It was modern fiction when it was written –and pretty hip, at that. Fitzgerald didn't set the book in a time other than his very own!

That said, if books for young people with a historical setting are getting short shrift because of the term "historical fiction," then maybe some re-branding is in order. Maybe publishers could call it "retro fiction."

Kelly, thanks – The Great Gatsby wasn't a good example – and I get a smile out of "retro fiction." It's like Jen's "HisFic for Hipsters" at Reading Rants.

I don't usually read war books because I know they're likely to be emotional reads. I have to steel myself for what might happen and I usually end up sobbing my eyes out (like I did with Code Name Verity). So for me, it's not because war books = historical fiction. I don't have a problem with historical fiction, I've enjoyed reading a number of books under that genre. But I think it's different for me because I'm based in the Philippines – our required reading for school were not labeled as historical fiction.

Also, thank you so much for linking to my review! 🙂

@ Chachic: I agree – it's a lot of the time because I don't want to cry!!

So, in school in the Philippines, you weren't assigned to read fictionalized accounts of history because those were considered entertainment, or because Philippine authors did not fictionalize history when you were a kid?

Historical fiction as being used for classroom assignments is something that has been very popular and not at all popular – in grad school, we listed the sort of "instructional" fiction that existed and discovered that most of what was assigned to be used in schools *was* so-called "historical fiction" – a lot of teachers didn't see value in just a regular story.

I'm always interested in how schools work in other places and cultures.

Oh we did read fictionalized accounts of Philippine history but for some reason, they were not labeled as historical fiction. All schools here are required to teach the novels written by Jose Rizal, our national hero, which are set during the time when the Philippines was still colonized by the Spaniards. I think we mostly think of that as just "required reading" instead of "historical fiction." Maybe that's why when I think of historical fiction, what usually comes to mind are novels set in foreign countries?

@ Chachic: Oh, interesting! Historical fiction to me is always American history — and that might explain to me why CODE NAME VERITY to me doesn't seem that way to me at all – it's just deeply exciting, troubling, and dramatic.

Hmm!

(And now I need to look up Jose Rizal!!)

Amen, Tanita! You said it!

Finally catching up on this discussion…I'd normally characterize myself as someone who says "meh" when it comes to so-called historical fiction–but then I think about Ann Rinaldi, who wrote some pretty interesting stuff, and Ten Cents a Dance by Christine Fletcher and Al Capone Does My Shirts…and it doesn't have to provoke this yawn reaction, obviously. And I remember a few years back when people were telling me that, with teens, historical fiction was BIG. I think booktalking DOES have a lot to do with it–along with, of course, a great story. As you said, Tanita, a great story stands by itself, regardless of its trappings.

Oooh, I found this post fascinating because I taught seventh grade ELA and history for a number of years, but got my degree in modern european history (since I couldn't create the major I wanted – which was basically historiography, or how history is written (and what history is), though that is what I wrote my thesis on. )

Here's the reason I am one of those people that says they have issue with "historical fiction" as a genre. I am more than nerd about history, and I care passionately about it, which is why I wanted to teach it. But as a reader (and a teacher), I am immediately dragged out of a story when I come across something grossly inaccurate. It;s like some people get when they read things that don't have proper grammar, or they are sports fans and the book states that Green Bay beat San Francisco in 1998, but the reader knows for a fact they didn't. Why change that fact, when so often it is a throw away? (Don't get me started on Philippa Gregory, or authors calling the San Francisco International Airport "SFI" instead of "SFO" – RESEARCH IS YOUR FRIEND.) It all started with this book titled "Hitler's Niece" – and yes, he had a niece, but there is a record of him seeing her only once or twice during the war, and the novel goes on to state all these things about Hitler as fact – which aren't. So why not create an original character? An SS commandant or something? The movie "The King's Speech" was excellent – but King George didn't give his first speech over the radio at the start of the war. He did it three years before at a large gathering. I understand it makes the story more intense by switching the timing, but now there's loads of people running around thinking that King George got over his speech impediment right at the moment his country needed him the most for his first war time address – and it's not fact.

Americans are absolutely lousy at history. We can't find things on maps. And we aren't doing ourselves any favors by not even trying to get things correct sometimes. Or go ahead and take some creative license, but please, at least make an EFFORT to get some factual history in there.

I do believe a great story is a great story, so why do you need the trappings of putting in actual people, or fictionalizing real people with real histories? History is so subjective as it is, and it *is* so difficult to get people interested in history, that when you do, why do it wrong? I can't tell you how many people tell me they know things are fact because of movies and books and they are quite simply absolutely wrong.

Take CODE NAME VERITY. Ormaie does not exist. The situation, as told, never happened. But the details did. There were people exactly like those characters – but Wein didn't have to use their names to make it "historical". I guess what I mean is, I have no problem when fiction is treated like fiction, but I take issue when fiction is treated as history.

(I taught Night by Weisel multiple times, and since I was teaching at an alternate assessment site, my students were not at-grade level reading. We did part of WWII by reading Sadako and the Thousand Paper Cranes.)

I guess that is my point – I believe fiction can complement history, but it shouldn't be used to teach history alone. (One the best books I think out there for teaching about pre-industrial England is Elizabeth Bunce's "A Curse as Dark as Gold." And that's a retelling of a fairy tale, so clearly you can do things from a lot of different angles. You just can't be LAZY about it. You have to care and have a reason for setting it during that time.)

I will stop now. 😉

@ Alaska: I'm glad you stopped by. I very much agree – you cannot possibly use fiction alone to teach fact – but you can certainly use it to enhance and to make accessible historical periods, facts, or specific themes. For myself, I know that were I to preface Britain's struggle mid-war with CODE NAME VERITY, my students would be reading more closely for facts and incidents which matched the book – thus reading their history texts and supporting documents more closely, which could only be A Good Thing.

One point I can quibble with you on, however; I've lived in the UK now for almost five years. It seems that the U.S. is not the only one poor at geography and map skills; in the modern world, where the go-to is either Google or your iPhone, people don't mentally retain facts; I think there's a generation being trained to do without referencing their brain for anything like phone numbers or email addresses. History by definition must exercise something other than our short-term memory… so, how to engage students with that, when short-term is even slipping past? This is not a "O, woe!" kind of statement, but a pondering, really, and an acknowledgement that lazy teaching really isn't going to work to anyone's advantage in this brave new tech world…