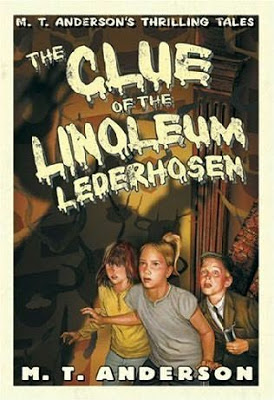

The author M.T. Anderson has long been one of our favorites here in the Wonderland treehouse — perhaps best known for the iconic 2002 YA novel, Feed, or for his hilarious middle-grade book Whales on Stilts! More recently, we’ve been wowed by The Astonishing Life of Octavian Nothing, Volumes 1 and 2. Mr. Anderson is an amazingly accomplished writer; his YA work is stunningly intellectual, amazingly versatile, and–perhaps most important–just plain absorbing to read. We are in awe, and we’re so not worthy–which is why we’re so proud to present this incredible in-depth interview with Mr. Anderson as part of the 2008 Winter Blog Blast Tour.

The author M.T. Anderson has long been one of our favorites here in the Wonderland treehouse — perhaps best known for the iconic 2002 YA novel, Feed, or for his hilarious middle-grade book Whales on Stilts! More recently, we’ve been wowed by The Astonishing Life of Octavian Nothing, Volumes 1 and 2. Mr. Anderson is an amazingly accomplished writer; his YA work is stunningly intellectual, amazingly versatile, and–perhaps most important–just plain absorbing to read. We are in awe, and we’re so not worthy–which is why we’re so proud to present this incredible in-depth interview with Mr. Anderson as part of the 2008 Winter Blog Blast Tour.

Finding Wonderland: You’ve blown us away with the scope of your writing – vampire YA novels, picture books, MG thrillers, biographies, for middle grade readers and young adults. Would you consider OCTAVIAN NOTHING and its sequel to be your “adult” types of books? Is there any kind of writing that you haven’t attempted that you want to try?

M.T. Anderson: I do believe the two OCTAVIAN books could have been published for adults–but I really did feel firmly committed to selling them as teen books. That’s the audience I was most excited about reaching.

As for other genres…I’ve published short stories for adults, and I’ll probably go back to that form at some point. I would like to do some adult nonfiction work as well. Perhaps something about the international garment trade, which has always struck me as a system to which we don’t pay enough attention.

I’m not really sure I’m cut out to be an investigative reporter, however. Can you be a polite, neurotically amiable investigative reporter? “I’m reeeeeeally sorry for bothering you, and I hope you don’t think I’m a big jerk, but, um, aren’t those toddlers sewing your gussets?”

I’m not really sure I’m cut out to be an investigative reporter, however. Can you be a polite, neurotically amiable investigative reporter? “I’m reeeeeeally sorry for bothering you, and I hope you don’t think I’m a big jerk, but, um, aren’t those toddlers sewing your gussets?”

…eh, okay, so the investigative thing probably won’t work out. But we’d read it if you wrote it!

FW: Your use of narrative language in the Octavian Nothing books is accurately reminiscent of the 19th [18th, I hope!] century style, mind-blowingly accurate, actually, for a modern novel. What type of research did you do in order to create a voice for Octavian—and for the other characters–that was authentic to the time period? Were there any particular difficulties about voice that came up during the writing of these books?

MTA: Well, first I should say that it was incredibly important to me that the voices feel accurate, because I truly believe that not only are we defined by our language–our world is defined by it, too. To fully commit to the strangeness of another time, another place, you need to commit to the quiddities of its language.

So for the Octavian books, I immersed myself in 18th C poetry and prose. While I was writing this story, I didn’t read anything except books written in the 18th C, books written about the 18th C, and older books they would have read in the 18th C (translations of Greek and Roman classics, etc.). I really wanted to ensure that I was infused with that antique prose so that naturally, as I wrote, I’d use 18th C grammatical constructions. I also created a huge file in which I noted differences between 18th C language and modern English.

I don’t think I need to say that, though this ensured that I was immersed in the period, and though I got to read some amazing books this way–things I never would have found otherwise–I also kind of ran out of top-drawer stuff to read after several years, and ended up slumming through some pretty awful dreck. Lots of pallid heroines and wicked seducers.

So I was incredibly relieved when the stint ended and I suddenly could go through a period of linguistic decompression (so I wouldn’t get the bends)…Reading 19th C books…and then, before I knew it, crime fiction from the 30s and 40s…My god, they were wearing actual pants! It was bliss!

FW: (Hah. Could see how the flashes of pale ankles and the lack of pants would get old after awhile.) Your 2002 dystopian novel, Feed, also had a very distinct voice and use of language (which you describe at the 7-Imps as a “linguistically impoverished, dumb-ass style” which made us almost spew coffee). What made you choose a first-person narrator in that instance, and why did you decide to write in a perhaps risky form of imagined future slang?

FW: (Hah. Could see how the flashes of pale ankles and the lack of pants would get old after awhile.) Your 2002 dystopian novel, Feed, also had a very distinct voice and use of language (which you describe at the 7-Imps as a “linguistically impoverished, dumb-ass style” which made us almost spew coffee). What made you choose a first-person narrator in that instance, and why did you decide to write in a perhaps risky form of imagined future slang?

MTA: As I said above, I believe that the language we use not only defines us, but in some way delimits and infuses what we see in the world around us. In the case of Feed, I wanted the reader to feel claustrophobic–like there’s stuff s/he wants to find out about the future and how it works and how people are feeling, but the reader can’t, because everything’s channeled through this well-meaning doofus.

Our ability to recognize subtleties of thought and emotion are tied to the words we know and can use. Characters who only register a paltry set of emotional indicators (sad, happy) are going to be less likely to recognize the full complexity of what they’re feeling when, say, some girl they’re going out with is mentally and physically deteriorating. So it was very important to me that the language not just tell the story, but also hinder the story from being told.

FW: We really like your idea on language limiting/delimiting… speaking of limitations, all of your novels have been from the point of view of …basically white males, and even in one case, an undead white male.

MTA: Ha! LOL.

FW: …Octavian is a serious departure. Have you gotten any flack for writing in the “exotic” voice of an African American male? Would you care to comment on writers stepping outside of their gender, class and ethnic boundaries to voice characters?

MTA: I haven’t gotten any flack about writing across race, but it was conceptually something I was extremely wary about. I stalled in the planning stage of the book for some months and seriously tried to reroute the plot so it wasn’t about Octavian…but to me, he was the story. He was the voice. Even when I knew nothing else, I knew him. It was his tale I wanted to tell. So I went ahead with it, despite all the pitfalls I may have stumbled into. The readers will have to decide whether I did his story justice, whether he is credible as a character.

MTA: I haven’t gotten any flack about writing across race, but it was conceptually something I was extremely wary about. I stalled in the planning stage of the book for some months and seriously tried to reroute the plot so it wasn’t about Octavian…but to me, he was the story. He was the voice. Even when I knew nothing else, I knew him. It was his tale I wanted to tell. So I went ahead with it, despite all the pitfalls I may have stumbled into. The readers will have to decide whether I did his story justice, whether he is credible as a character.

FW: So, where did the character of Octavian Gitney come from? What was the inspiration behind the disturbing but interesting Novanglian College of Lucidity — is it based on Ben Franklin’s American Philosophical Society, or is it completely fabricated?

MTA: The voice of Octavian Gitney sprang fully-formed into my head. He seemed very present right from the beginning of the project, despite, as I’ve said above, the fact that I tried to shift the story to be about someone else. The idea for Octavian’s initial predicament came from a half-remembered story about how a similar experiment was undertaken at Cambridge University in the 18th C, under the auspices of the Duke of Montagu. The anecdote captured my imagination–the whole idea of these Enlightenment scholars in that dank, murky university in the midst of the dismal fens working away by candle-glow, believing that they were illuminating the subject of darkness and light while in fact being blind to their own weird biases and ceremonial culture…It fascinated me, and I felt immediately as if I knew the boy who’d result from those experiments. (Though Octavian didn’t in the end really resemble Francis Williams, the actual subject of Montagu’s putative experiment, beyond a shared knowledge of Greek and Latin…)

After some consideration, I decided to set the story in America, rather than in England. The College of Lucidity is indeed based to some extent on the American Philosophical Society, but I drew on experiments conducted throughout the Americas and Europe at the time. All of the bizarre scientific research I mention is based on real investigations from the period. I culled things from histories of similar institutions, from the 1771 Encyclopedia Britannica, and from delightfully weird 18th C scientific papers archived at the Boston Athenaeum.

Science is so vibrant, so strange in the period. They have not yet learned to separate disciplines and to expunge human concerns, emotional concerns, and even theological enthusiasm from their experimental discussions. That’s what makes their science writing such a refreshing delight to read. For example, John Winthrop, a Harvard professor, wrote a pamphlet on the Transit of Venus as he observed it in Newfoundland. He doesn’t just record data about the movement of the spheres, however: He also complains about the mosquitoes and fly-season. He ruminates on how God is illuminated by this study of the heavens. He comments on the sublimity of these Transits happening with such irregularity: “…When this [one] is past, the present race of mortals may take their leave of these Transits; for there is not the least probability, that any one who sees this, will ever see another.”

Science is so vibrant, so strange in the period. They have not yet learned to separate disciplines and to expunge human concerns, emotional concerns, and even theological enthusiasm from their experimental discussions. That’s what makes their science writing such a refreshing delight to read. For example, John Winthrop, a Harvard professor, wrote a pamphlet on the Transit of Venus as he observed it in Newfoundland. He doesn’t just record data about the movement of the spheres, however: He also complains about the mosquitoes and fly-season. He ruminates on how God is illuminated by this study of the heavens. He comments on the sublimity of these Transits happening with such irregularity: “…When this [one] is past, the present race of mortals may take their leave of these Transits; for there is not the least probability, that any one who sees this, will ever see another.”

He mentions that one of the next times anyone will be able to observe what he saw, it will be the unimaginable year 2004…and suddenly, there is an eerie connection between this very particular day in 1761, a Harvard man sitting on a hill, bitten by “infinite swarms of insects,” peering through ground lenses…and our own time, our own thirst for knowledge as yet still unfolding.

FW: That is just immeasurably cool! We can see now how the whole thing caught at your imagination. You have often said in other interviews that you struggle with plot, and that the editor’s revision suggestions in your first novel, THIRSTY, were mainly that you “add a plot.” How do you confine yourself to plot as a character-driven writer? What are the first things you do to help put together a coherent storyline? (Other than the broccoli. We’ve heard about that, with more than a little disgust.)

MTA: As the years have gone on, I’ve become more comfortable with the idea of plot, especially because a lot of my writing (even the Octavian books) feeds off genre writing of some kind.

I’ve arrived at my stories from several different directions. In some cases, I let little fragments of things I hear about or read about coalesce, and suddenly, there’s some kind of scenario suggested…The Octavian plot above being one of those examples. I stuck that set of details together with a description of historical “pox parties” (inoculation and quarantine parties held for the smallpox in the 18th C) and suddenly, I had the primary scenes of something…and then all I had to do was connect the dots.

I’ve arrived at my stories from several different directions. In some cases, I let little fragments of things I hear about or read about coalesce, and suddenly, there’s some kind of scenario suggested…The Octavian plot above being one of those examples. I stuck that set of details together with a description of historical “pox parties” (inoculation and quarantine parties held for the smallpox in the 18th C) and suddenly, I had the primary scenes of something…and then all I had to do was connect the dots.

In other cases, I’ve tried to come up with the entire plot ahead of time. In graduate school, for example, I knew vaguely that I wanted to write about my time working at McDonald’s. But I didn’t have a plot. I was reading a lot of Jacobean Revenge Tragedy for school at the time, and I figured, Hey! All those doublet-and-hose bastards are always stealing plots from ancient sources. I’ll just steal a plot from them. So for an evening, I paced around in circles (see above), trying to conform The Revenger’s Tragedy to a burger restaurant.

Nothing doing. There was too much murder, incest, and destruction. It was just grotesque. I wanted to do something lighter. So I decided to take the primary elements of a Jacobean Revenge Tragedy–a main character, wronged, cuckolded, named Anthony–a kind of a burger court–the feints at friendship, etc.–and I just forced myself to come up with a set of events where A led to B led to C. I wrote out an outline, scene by scene, detailing the precise function of each and every interaction. Then all I had to do each day was the fun stuff–the dialogue, the weird asides, the descriptions of my beloved suburb, etc. (Though I didn’t, incidentally, stick with the outline all the time. Occasionally I changed things along the way.) It was some of the most fun I’ve ever had writing a book. Many of the minor characters, incidentally, are named after the writers of Jacobean tragedy as an homage to the plays that inspired me.

FW: What initially attracted you to the time period of the American Revolution, a series of events that seem so simple and righteous and straightforward and even inevitable in our history books, but in fact were ambiguous and contradictory?

MTA: Mainly growing up outside of Boston during the Bicentennial. All that history was right at my fingertips. I felt like it was important to investigate what it felt like to fight in that war before the myths were made, before the end was known. The true measure of the heroism demonstrated is not the legendary verities we associate with the Founding Fathers–but rather the intensity of their doubt. They didn’t know how it was going to turn out, and yet they fought on. So to my mind, looking at this moment of doubt and unclarity is a way of restoring heroism to decisions that were not easy and were, in some cases, fatal.

FW: Pseudosciences like craniology and phrenology in the 18th and 19th century were once used as a basis for scientific racism that dealt with the inability of certain races to have intellect – thus the bizarre depiction of “happy darkies” that the Gone With the Wind group loved so well. With as much 18th century reading and research as you did, was it difficult to find reliable information about slaves and former slaves during this period? What were some of the pleasant surprises that you found in your research, or were there any?

MTA: It took a very long time to gather information on slave life in the period–especially because the structure of slavery varied so much from place to place and decade to decade. (For example, the Antebellum plantation of myth that appears in Gone With the Wind is a model based on 19th C cotton production…whereas, in the 1770s, cotton wasn’t yet an important crop. There were other staple crops with their own associated social and administrative structures.) Furthermore, the question of how historians reconstruct slave life is extremely complex, given the unreliability of written sources and the obscurity of the archeological record.

There weren’t, of course, many pleasant surprises in this research. Most of what I found was soul-destroying. But I did discover that each system, each region had its pros and cons. For example, in the Deep South and in some parts of the English-speaking Caribbean, slaves may have been given somewhat more autonomy when it came to domestic arrangements and food production than they were granted in the Tidewater region…The system in Virginia and Maryland was more paternalistic, which meant that your owner theoretically provided for you, but you were watched more carefully….On the other hand, the reason that slaves in the Deep South had a little more autonomy was that their masters didn’t want to be anywhere near rice and indigo plantations that bred disease and smelled like hell. …And of course, wherever you were, violence was always an ever-present threat.

Um, sorry. That was still kind of a downer, wasn’t it? (Um, a lot, yes…)

I guess one cool thing was to read about the survival and transformation of African practices on American soil–the use of circular house-forms on some plantations in the Deep South, for example, or Asante charms found in slave quarters in Boston. Less of that survives than one might like–but still, it’s a testament to the strength of the human spirit.

I guess one cool thing was to read about the survival and transformation of African practices on American soil–the use of circular house-forms on some plantations in the Deep South, for example, or Asante charms found in slave quarters in Boston. Less of that survives than one might like–but still, it’s a testament to the strength of the human spirit.

I suppose the most fun I had with this research was reading translations of African material to get a feel for some of these cultures before the diaspora. Here, for example, is one of my favorite Yoruban poems. It’s about a chicken:

One who sees corn and is glad.

Happily eating the worm,

unaware of her fate…

The foolish chicken has many relatives:

oil is her uncle on the mother’s side

pepper and onion are her aunts on the father’s side

pounded yam is her in-law.

If she does not see her friend salt for a day

she does not sleep peacefully.

Not only humor but a kind of recipe! That’s disarmingly hopeful.

FW: Many of your books are about the negative things that happen as a result of groupthink. Octavian is definitely no longer one of the group – highly educated and nurtured in the bosom of frock-coated and genteel society, he now stands out as he makes his way through the world outside of the College, not able to feel entirely at home with either the Revolutionary soldiers or the former slaves in Lord Dunmore’s Royal Ethiopian Regiment. Did you have a particular reason for creating a character who was clearly an outsider in nearly every milieu? Did that make Octavian a more effective observer, more of a philosopher?

MTA: Yes, that independent viewpoint was important. But equally important (if kind of vague!) is that I simply imagined him that way. That’s who he seemed to be.

FW: It’s always fun to talk to someone whose use of language makes you think while he talks, think while you listen, and possibly use a dictionary just to check a few things when he’s done. Mr. Anderson, thank you sincerely for your thoughtful, thorough answers to questions you’ve probably gotten again and again. We very much appreciate you stopping by. Also, thanks to Cynthia Leitich Smith for helping us get in touch with him, and Tracy Miracle and Nicole Deming at Candlewick Press for their continued cheerful assistance.

To read more about M.T. Anderson, check out the following links:

NPR interview, Nov. 2006

Q&A with Publishers Weekly

Cynsations interview with Cynthia Leitich Smith

Seven Impossible Interviews Before Breakfast #13

Hey, readers – thanks so much for coming by and commenting and reading, and picking up these authors’ books and loving them as much as we do! We do these Blog Blast Tours because books are full of awesome, and they are an inexpensive luxury item that makes a great gift!

Hey, readers – thanks so much for coming by and commenting and reading, and picking up these authors’ books and loving them as much as we do! We do these Blog Blast Tours because books are full of awesome, and they are an inexpensive luxury item that makes a great gift!

It doesn’t seem possible, but the book talking tours are still going strong! Check out more amusing, intellectual, quirky authors and their books at:

Ellen Klages at Fuse Number 8 @ SLJ

Emily Jenkins at Writing and Ruminating

Ally Carter at Miss Erin

Mark Peter Hughes at Hip Writer Mama

Sarah Darer Littman at Bildungsroman

and our own Mitali Perkins at Mother Reader.

**BONUS author interview at A Chair, A Fireplace & A Tea Cozy.

Thank you very much for including my interview on the list! Christine & I both appreciate it!

Let me say that: 1) You almost lost me at “in-depth” because I consider myself much more superficial, but it is MT Anderson so I was happy to continue. 2) I opened a RTF to write this comment as I read, something I’ve never done before now. 3) I had to look up “quiddities” in Dictionary.com to see if it was a real word. 4) It is. 5) Ditto “Jacobean Revenge Tragedy” 6) But in Wikipedia. 7) Scrolling down I wonder, “Why is there a chicken picture?” 8) Oh. Chicken poetry. Should have guessed. 9) Thank god I didn’t ask to do this interview because this is far, far more intellectual, interesting, and intriguing than I could have managed. 10) That’s intended as a compliment to both interviewer and interviewee. ( 11) I also had to look up compliment to make sure it was the one with “i,” not “e.” Nailed it!)

Boy, I love this man! (Shhhhhhh! Don’t tell my husband!) I would love to crawl into his head for a day. What a trip that would be!

Thanks for an amazing interview.You guys rock!

I’m with Tricia. Thanks for asking such great questions. Man, he is awesome.

Yup, me too – awesome interview, and the pictures just *make* it.

I’m neglectful; I’ve never read anything my MT Anderson. I will have to rectify that. Good interview!

Well, my day has been made to read an interview with M.T.

And, oh my, how difficult it must have been to let the language tell the story in FEED, while — at the same time — let it hinder the story from being told. I have even more respect for him as a writer now. (And, of course, I want to re-read the book.)

Thanks for the interivew!

Jules, who still has yet to start OCTAVIAN II — god, I’m slow these days…

Oh, this is such a terrific interview. I’ve just finished Octavian II and I’m having a little bit of an MTA withdrawal, so this helped take the edge off a bit. Now to go back and read the other interviews as well!

feed = best book I made my book club read. (I’m obnoxious in my proselytizing for this title.)

Octavian Nothing = was in book love from the first paragraph. The sequel is right here on my desk, as my reward for revisions accomplished.

I gave Whales on Stilts to my niece and nephew and they loved it.

But I can’t believe I haven’t read Burger Wuss yet. What a wuss I am. (I worked at Pizza Hut as a teenager—that must be it.)

Thank you for seeking out this interview. It was fabulous.

What an amazing interview!

When I attended a booksigning with Laurie Halse Anderson recently, she was asked the same question about writing an African American character as a white person, and her reply was similar to what Mr. Anderson says here. She also mentioned how startingly intellectual and intelligent he is, that whenever she converses with him, she has to kind of sit back and just try to absorb for awhile; her mind reels.

Best of all, she wondered what was up with the M.T., since everyone calls him Tobin.

Thanks to this interview, I understand better what she was talking about!

These were really fabulous questions!!

Great interview! And even though Liz said it already, I’ll say it too – Thanks so much for including our interview on your list.

Thanks, guys! I have to tell you, we felt honored just to do the interview. Sara–I haven’t read Burger Wuss yet, either, but I’ll definitely have to.

TadMack, your extra images and pull quotes totally rock! 🙂

But, Mother Reader, didn’t you feel better when he said “LOL”?

I saw M.T. speak here in town a month or so ago, and he read a bit out of Feed and a bit out of the first Octavian Nothing book, and he’s a darned good reader. I especially enjoyed his rendition of the teenage girls in the first couple scenes of Feed.

Wow. And squee! And wow, again. This interview so rocked.

Liz & Christine: You are SO welcome!

MotherReader: Hee! But, see, now you can totally drop quiddities into your next philosophical conversation!!

The fun part of all of this is I haven’t read all of his MG books yet, and some of the rest of you missed the oldies like Burger Wuss, and Thirsty. There’s more fun to be had! No withdrawals necessary!

This is a remarkable interview. What reassurance to read about his struggles with and through plot, and his triumphant overcoming. And very funny to imagine him slinking about as an investigational reporter. He has a new story due out in a HarperTeen anthology next May, a book called No Such Thing as the Real World. Extremely innovative, again.

Must read Octavian, have read Feed and Whales on Stilts (hilarious). Feed was moved from the middle school to high school last year. A sad state of affairs.

Great interview the Octavians are must reads!

Logan Lamech

http://www.eloquentbooks.com/LingeringPoets.html

Ladies and Tobin, this was a fabulous interview to read. I’m also getting the itch to reread Feed… and Thirsty… and Burger Wuss…

Also, my word-verification test for this comment is “skerv,” which I think I’m going to adopt as an actual word. It sounds like a contraction for “skeevy pervert,” as in: “Ew! Did you hear what that old dude outside the adult theater said to me? What a skerv!”

Eisha, you CRACK ME UP.

Skerv. Such a great word!!

LOVED this interview. Fantastic.