Welcome to another session of Turning Pages!

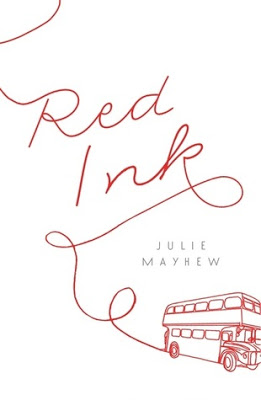

Synopsis: Snarky, brittle, awkward, British-Greek teen Melon Fouraki is fifteen and unmoored after her mother is hit by a bus. Despite them going away to Crete every summer, somehow Melon never was introduced to any of the grandparents, aunts or uncles who passed in a blur before she was dragged off to yet another beachfront hostel. East Finchley, Melon’s blue-collar neighborhood in London, has virtually no connections left for her except for her mum’s social worker mates — and her mother’s “partner” who is awfully broken up about everything, and apparently has a picture of her mother wearing a diamond ring…? Melon is a bit bitter that she hadn’t… noticed the ring. What? Her mother was engaged????

There’s a great deal that Melon hasn’t noticed — that her “best” friend, Chick, is quite self-centered and unkind, that Chick’s parents can’t stand Melon and are in horrors of being left with her after her mother’s death, and that her mother has created a narrative for their lives in London that’s long on lyricism, but not exactly detailed, and explains exactly nothing about why there are few, if any, pictures of Melon’s babyhood, no pictures of her father, and little communication with the Fouraki family… but it’s the story that Melon knows the best. The Story. The tale of her mother’s childhood, of the reason she’s named “Melon.” The story of her missing father, the Fouraki feud with his family, and the reason for the distance from the family back in Crete. The Story is Melon’s origin story, the story of how she, and her mother, Maria, came to live in East Finchley. With the holes left in Melon from grief — and rage, because her mother was offbeat and hard to predict, and their relationship suffered from Maria and Melon’s self-absorption — The Story is all Melon has left that tells her who she is, and who she has the capacity to be. But is The Story everything Melon’s mother could have told her? And, can a grief-stricken, resentful, dead-ended Melon pull herself together to write herself a new chapter, so that she can go on without Maria?

Observations: The characterization of a British teen reads as spot on for me. Melon’s shock-oriented “I’ll say anything” attitude, occasional potty mouth, and bitterly blasé attitude toward school, adulthood, and authority is familiar to those who enjoy contemporary English or Commonwealth YA authors. One doesn’t often read novels about people who’ve landed in care due to the death of a parent, and the sort of bewildering trail of social workers and bereavement counselors – and Melon’s indifferent reaction to them all – would be in some sense atypical for an American teen, as there is much more… institutionalized anxiety, as it were, about kids in the foster system due to a lack of family. Melon’s time with the bereavement counselor is especially amusing, as she repeatedly articulates her confusion that everyone is so broken up about her mother’s death, and resents feeling an expectation to weep and be upset when she feels not much of anything except resentment at the inconvenience, and that no one knows what to do with her. Melon just wants to hold out until she’s sixteen and can leave school. Unfortunately, she has several months to go, and is stuck with her mother’s partner, Paul, until then, as he’s the only one who wants to deal with her, and frankly, Melon’s not sure about that.

Observations: The characterization of a British teen reads as spot on for me. Melon’s shock-oriented “I’ll say anything” attitude, occasional potty mouth, and bitterly blasé attitude toward school, adulthood, and authority is familiar to those who enjoy contemporary English or Commonwealth YA authors. One doesn’t often read novels about people who’ve landed in care due to the death of a parent, and the sort of bewildering trail of social workers and bereavement counselors – and Melon’s indifferent reaction to them all – would be in some sense atypical for an American teen, as there is much more… institutionalized anxiety, as it were, about kids in the foster system due to a lack of family. Melon’s time with the bereavement counselor is especially amusing, as she repeatedly articulates her confusion that everyone is so broken up about her mother’s death, and resents feeling an expectation to weep and be upset when she feels not much of anything except resentment at the inconvenience, and that no one knows what to do with her. Melon just wants to hold out until she’s sixteen and can leave school. Unfortunately, she has several months to go, and is stuck with her mother’s partner, Paul, until then, as he’s the only one who wants to deal with her, and frankly, Melon’s not sure about that.

Women are very important to this narrative, and the strong women who are Maria’s friends have Melon’s respect, after her mother’s death. The men in the novel – Melon’s grandfather, uncle, and father – are largely immaterial; Melon finally noticed her mother’s coworker, Paul “around,” and the niggling issues she (and her Greek relatives) has with him are borderline racist, but mainly unexplored, as if the tensions don’t exist. Though he’s been “around” for more than a year, and though Maria has stipulated in her will that Paul will care for Melon if something happens to her… Melon is caught off-guard by his grief, and his presence. This willful ignorance is something which both Maria and Melon share; Maria ignores that people laugh at Melon’s name and that her daughter is struggling at school with being bullied by boys mocking her shapely body, and Melon ignores… pretty much everything about her mother. They live in a state of armed siege, and then the siege is broken unexpectedly – and unfairly, to Melon’s point of view.

A lot of this novel is about identity and omissions – life, and its lies. Near the end of the novel, Melon, after finding out news that simply guts her, has an encounter with a boy which is essentially non-consensual. As many do during an assault, she lies to herself as it happens – continuing the storytelling-as-coping-mechanism her mother was so good at — re positioning the narrative to reflect what she chooses to see. Interestingly, Paul corrects this tendency toward denial and asks Melon straight out for the factual version of events (leaving the reader wondering if he managed Maria in the same way). Through her own bitter experiences with truth, Melon begins to value that a story is not, at times, entirely factual. At the end of the novel, she realizes the uses of a permeable truth and begins the work of forgiving Maria, most tellingly by seeking that kind of truth about her mother’s life, as seen through the lens of her other Greek relatives. The big picture takeaway of the novel is that truth sometimes matters less than perspective, especially when dealing with family history. Everyone has their own Story, and Melon begins to come out of her extreme self-absorption and notice this simple fact.

Conclusion: Written in flashbacks, the non-linear style of the novel reflects the circuitous versions of The Story which keep Melon’s understanding of her identity encapsulated. Melon’s Story flows from the author’s pen with a lyrical style, a beautiful tale to reassure a child. But a pretty story isn’t what most of us need to live and grow, and Melon’s ragged brashness the bright light of perspective on truth, lies, and the need to create a self without our parent’s storyline.

This book was first published in the UK in 2013. I received my copy of this book courtesy of Candlewick Press, and now you can find RED INK by Julie Mayhew at an online e-tailer, or at a real life, independent bookstore near you!

I just saw this one in the e-library and was intrigued. I'll have to read it!