I would have gotten to this book eventually, I think, but because Linda Sue Park mentioned it on her Beacon St. TEDx talk (and if you haven’t had a chance to watch, please do) which was so full of good thoughts, I bumped it immediately to the top of my TBR list.

I would have gotten to this book eventually, I think, but because Linda Sue Park mentioned it on her Beacon St. TEDx talk (and if you haven’t had a chance to watch, please do) which was so full of good thoughts, I bumped it immediately to the top of my TBR list.

I laughed at some guy on Goodreads saying “police brutality is not my usual thing” – um, no, it should be NO ONE’s usual thing, duh. A book in which I KNOW someone is going to be badly hurt is not something I want to read on a normal day, but I knew I needed to, as I’ve sort of eavesdropped on the chatter going on in the Twitter kidlitosphere and realized how many people are too terrified to talk about things honestly, how many people are sitting around waiting to leap to conclusions and point fingers at people who do try to talk honestly, how often emotions are invalidated, and how few people are able to listen and are able to hear and not be offended, or let another person’s truth guilt them into lashing out. In short, we are a hot mess when we talk about race, even in the kidlitosphere. I wanted to read this book so I could suggest it to others.

More personally, I wanted to read this book because I think it was written, in part, for someone like me. I grew up with a heavy emphasis on respectability politics, was given “the talk” on how to navigate situations with law enforcement repeatedly. The basics? You’re already in the wrong if somebody looks at you sideways; shut up, keep your hands where you can see them, and keep your head down. Like Rashad’s father, I had this idea that racism could be reasoned with, if you just wore the right clothes, didn’t sag your pants, did your hair nicely, or didn’t wear too flashy of a manicure. However, the many, many, many, many people for whom this did not prove to be true – from Rodney King onward – slowly began to convince me otherwise. And, with that crutch of an idea gone, everything felt crazily… unsafe.

I imagine many teens are feeling like that now, and I want to hand them this book. I want to hand it to their parents. No, it doesn’t have the answer within, but it’s valuable because it begins the discussion on racism and injustice in a clear and calm way that many people are too hysterical – too fearful, too hostile, or too passive to think about without being primed. This book is an excellent primer.

Summary: JROTC cadet, basketball player, and Friday afternoon relieved Rashad – his mind on anything but trouble – is squatting down to pull his phone out of his bag in a corner store when a white lady trips over him. Possessions go flying, glass breaks, and he’s accused of theft. The police officer who happens to be in the store has him down in a headlock before he knows what’s up. Protesting his innocence – writhing in pain and being mistaken for someone resisting arrest – Rashad is —

Summary: JROTC cadet, basketball player, and Friday afternoon relieved Rashad – his mind on anything but trouble – is squatting down to pull his phone out of his bag in a corner store when a white lady trips over him. Possessions go flying, glass breaks, and he’s accused of theft. The police officer who happens to be in the store has him down in a headlock before he knows what’s up. Protesting his innocence – writhing in pain and being mistaken for someone resisting arrest – Rashad is —

— someone who looks familiar to Quinn, being beaten to a bloody pulp, right in front of him. Frozen like a deer in headlights, Quinn hopes Paul – his best friend’s big brother, who’s been looking out for him since his Dad died overseas – doesn’t know he’s there, watching him beat down that black kid. Quinn just wants to get out of there, blow it off. NBD, right? Only it is a big deal. It turns out it’s the biggest deal there is.

In alternating voices, Rashad and Quinn narrate the aftermath of an ugly incident, while they navigate an equally ugly truth: that there is no respectability which will save us from racism, it’s the uneven, pitted surface upon which American society uneasily rests, it didn’t disappear after the Civil Rights marches, and it’s not going to go away if we ignore it.

Peaks: This is an excellent conversation starter which I believe will challenge and inspire readers. It’s in many ways a straightforward, almost simplistic story, but in other obvious ways, there’s nothing simple about injustice. Rashad and Quinn, standing in for everyman, may be lost as individuals to some readers, and secondary characters definitely ghost in and out, as if they’re characters in a play — so some of the conventions of storytelling are done away with. Some may find this problematic, while others will find enough points where their emotional truths overlap to make up for this novel being more about concepts than characters.

I related in various moments to both characters — their desire at times to just not talk about any of this “race” stuff anymore, the realization that some people have the privilege to shut that off and walk away, and others don’t; the feeling of being angry that you’re angry about something you have no control over — all of these truly genuine feelings of helplessness and rage and resignation are there, and really resonate.

I’m always really happy to learn a new thing from a novel. Rashad is an artist who likes old Bil Keane cartoons and mentions artist Aaron Douglas — which prompted me to look up the artist and his stupendous work.

Valleys: This is less a valley than a choice – the authors chose younger readers as their audience, and chose to make Rashad blameless – ROTC, involved in a school sport, decent student. As a character, he is easily “defensible,” in some ways: he doesn’t do many things which a lot of kids do which people who indulge in casual racism can tick off as “problems;” Rashad doesn’t wear dreadlocks, doesn’t have friends who are gang affiliated, doesn’t shoplift, doesn’t have a record of any kind, never has so much as a Swiss Army knife in his pocket — so he is clearly not at fault in the incident, and the police officer who beat him down is easily described as having a history of violence despite his clean-cut “good guy” ways, so he is clearly at fault — clear, even from the perspective of someone who believes law enforcement personnel have superpowers and are always right. For some people, this may seem to be smudging an important point: that no matter WHAT, the penalty for shoplifting, back talk to a police officer, criminal trespass, etc., is not a white policeman beating up a black person of any age. I would hope that these finer points would be raised by adults reading along with a teen, but some people may feel the authors didn’t go far enough. As a door-opener, I feel this amount of information is plenty for a reader, and can too easily tip into being heavy-handed.

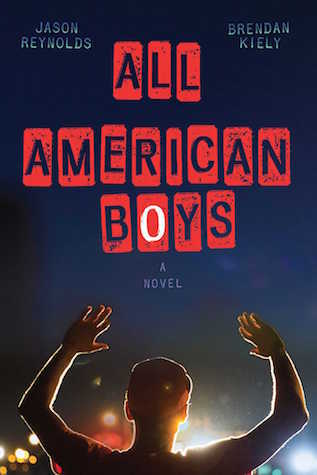

Cover Chatter: I really like this cover – for multiple reasons. Backlit, the cover model is anonymous, yet striking. I like that you can’t tell the color of the person standing below the title – he’s simply a creature of light and shadow, anonymous. On a quick glance, this might look like a sports or music star raising his hands, limned in light on the field of victory… but those are the wrong kinds of lights.

A funny thing about light — while it illuminates this kid in some respects, it also washes him out, erases his individuality — and makes him just another brown kid, in the police spotlight… Much is conveyed in this subtle imagery.

Conclusion: You know that average person who thinks that they have nothing to do with race or racism; who believes this whole black/white thing that’s been on the news recently is just uncomfortable and awful and we need to go back to “normal?” This is a book for them.

I checked out my copy of this book from the public library. You can find THIS BOOK by This Author at an online e-tailer, or at a real life, independent bookstore near you!