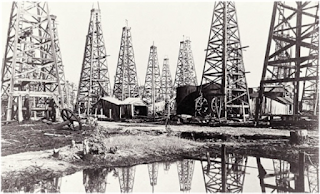

Happy Monday! We’re back again today with the final installment in our interview with the wonderfully articulate and interesting Ashley Hope Pérez, who has stopped by on her blog tour for her forthcoming novel Out of Darkness. The story is based on real-life events of the March 1937 gas leak which caused a massive explosion and killed almost 300 children and teachers at a school in New London, Texas. It also explores the fraught racial, cultural, and economic environment of Depression-era, pre-WWII small-town America.

In the conclusion of our interview, we talk about what effect writers can have in exploring stories like the one in Out of Darkness; what responsibilities authors might feel when writing a story that examines issues of race and violence, whether it takes place in the historical past or the present; and how writers decide to tackle endings that don’t conform to the traditional “Happily Ever After.”

Tanita Davis: Can reading books like OUT OF DARKNESS, which examines the racialized violence of the past, do anything other than provoke disdain for an ignorant history and ancestry and reinforce the idea that racism is a boogeyman from the past for teens who are allegedly post-race and colorblind?

Ashley Hope Pérez: For students who have not had the history of race relations in this country impressed on them (whether academically or in how they experience the world), I can imagine that there will be a desire to quarantine racism to the ward of “evils from history.” But I think readers can do more with Out of Darkness than that. I’ve already begun to suggest this, I suppose, when I said that Out of Darkness asks us to think about the present as well as the past. But you’re right that a lot depends on how readers receive the world of the novel.

Perhaps notions like “post-race” and “colorblind” do have relevance for some teens of color in some places, but for the most part it’s hard for me to imagine how anyone following the news—or just paying attention to the world around us—could believe race has no impact on contemporary experience. In my view, the notion of colorblindness has been a tactic of (often well-meaning) people who want to avoid the discomfort of talking about race. Other people have made better arguments than I can about why this is problematic, both for people of color and for well-meaning white people. You can see one example of this line of reasoning—that conversations of race matter for everyone, not just people of color—in this article about why and how to talk about race with kids.

TD: So maybe there’s an alternative reaction to racism as the boogeyman from the past…

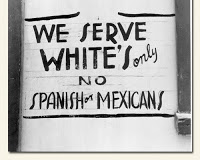

AHP: I think so. Although racism is rarely expressed as openly and directly today as we see it in the experiences of the characters in Out of Darkness, the novel can still attune readers to how racism and inequality persist in our world. The vulnerability of brown and black lives in public spaces is one example; another is the view that some loves are legitimate and some are not. I hope readers’ empathetic response to Naomi, Wash, and other characters primes them to embrace the precious humanity of people like and unlike themselves, especially when those people encounter discrimination or other injustice.

Sarah J. Stevenson: Do you see your book, or other books like it, as a call to action or a form of action in and of itself (or both)? If so –what did writing this book FEEL like you were doing, besides writing a compelling story? What do you feel is the author’s responsibility, if any, for making a social statement, and did you feel like you needed or wanted to convey a particular message? Did the act of writing this book feel like it ought to be a crusade?

|

| Photo of the 1937 New London school explosion |

AHP: I didn’t have a message in mind as I was first figuring out what the book would be. In the beginning and for much of the way, there was just the painful work of trying to draw my story out of a set of historical possibilities and one actual event. I did know, though, that my starting place for telling this story was not the white community, which has been the focus of pretty much every account of the New London school explosion. The heroes of Out of Darkness are people who, if they were real, wouldn’t even register in the official historical record. If I was crusading for anything, it was for the notion that these experiences at the margins of history matter. They matter deeply because every experience deserves a place in our understanding of the past. When we broaden our criteria for whose stories “count” in history, our notion of what the past was changes.

|

| An East Texas oil field, historical photo |

Authors have many responsibilities when they write, but I think any social statement has to grow out of the dynamics of the narrative; it can’t be imposed or decided in advance. Of course, plenty of writers have done this, but I don’t think it works. I think that, when I’m writing, my biggest responsibility is to pay attention to what the story is trying to become. When I revise, I revise to make my story more like itself, more what it wants to be. I realize that this sounds very mystical, so let me give an example.

Originally, I hoped for a different ending to Out of Darkness. I researched possibilities, charted escape routes, pondered the rare spaces in the world (Canada? The Caribbean? A black colony in Mexico?) where my characters might succeed in making their family. I wanted a positive outcome for Naomi and Wash, a future that, in spite of its challenges, was made bright because they were able to share it with each other. What happened? It wasn’t that this happy ending was impossible; as I said, I ferreted out some historical possibilities and tried to force it for a while. But ultimately that ending proved to be profoundly at odds with the story as it wanted to be. So even though the ending of the novel brings shade upon shade of darkness, even though it denies the reader’s desire for “Happily Ever After,” I believe writing it was my responsibility.

TD: And as tough as it was, at the end of the day, telling the true, and not rearranging for a “Happily Ever After,” is always the right call.

We are thrilled to have had this opportunity to have such a deep, meaningful conversation with the author about the book, about writing, and about the power of stories to help us forge connections with our own history, even (perhaps especially) when that past is uncomfortable or difficult. Thanks, Ashley, for stopping by, and a hat tip to her editor, too, the amazing Andrew Karre at Carolrhoda LAB. If you missed Part 1 or Part 2, just click the links! Also, Ash is over at Diversity in YA today with an essay which gives a bit more background on the hows and whys of her writing OUT OF THE DARKNESS. The essay is called, “Words That Wake Us.”