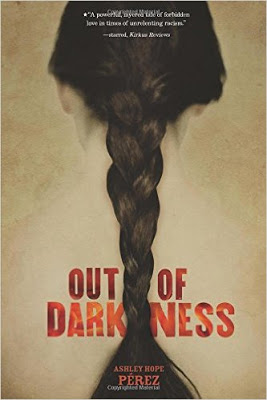

Welcome back to our conversation with author Ashley Hope Pérez, author of the forthcoming YA historical novel OUT OF DARKNESS, which is based on real-life events of the March 1937 gas leak which caused a massive explosion and killed almost 300 children and teachers at a school in New London, Texas. This is part two of our three-part interview.

OUT OF DARKNESS has been described as,“a powerful, layered tale of forbidden love in times of unrelenting racism,” while BookRiot’s Kelly Jensen calls it “powerful, painful, raw, and easily one of the best books I’ve read this year.”

It’s always great when a book receives a lot of quiet but intensifying buzz, as people all over the blogosphere begin sharing their experiences with it. Notable for its timeliness as well as its gut-wrenching love story, you also won’t want to miss:

- 8/5: A detailed review @ The Midnight Garden: YA for Adults,

- 8/9: A Q&A with Shelf Life @ U of Texas

- 8/10: Sarah’s Monday Review @ Wonderland.

- 8/12: An interview/giveaway @ YA Outside the Lines

- 8/17: A guest post on that elegant cover art @ Actin’ Up With Books,

- 8/21: A giveaway and 8/28 review and imaginary casting @ Forever Young Adult,

- 8/28: A review and exploration of history @ The Sarah Laurence Blog,

…as well as our three-part interview here, 8/28-31.

There’s a real beauty to this type of meandering blog tour, where bloggers get a real chance to actually discuss a topic in-depth. We as bloggers can take the time to do a bit more thinking so as not to trot out the same questions everyone else is asking, and this gives Ashley a larger platform for a deeper exploration of her work. There’s just a lot to explore, and a lot to discuss, so on that note – on with the show.

We rejoin the conversation, musing a bit on reading tough, uncomfortable books – and what we gain from reading them. Today’s conversation is both on reading — and writing.

Sarah J. Stevenson: In my experience, teens learn a lot from challenging their comfort zones, as readers and, of course, in life. Empowering and encouraging them to examine WHY they feel a certain way and learn to articulate it, rather than avoiding uncomfortable feelings entirely—that seems like a critical life skill.

Ashley Hope Pérez: A life skill and a way of exploring the ethical implications of how and why and what we read. This subject of “difficulty” or discomfort in reading is an area of overlap between my fiction, which makes some people uncomfortable, and my academic work, which often examines how difficult topics are handled in literature. Some treatments of violence, for example, are horrifying but cathartic in a way that lets readers “move on” from the tragedy. Other treatments don’t give the reader that kind of release. It’s terribly uncomfortable to be put in that position as a reader, and yet I also think it’s important. It’s important because it shouldn’t always be easy to “read past” suffering. I’d even say that reckoning with discomfort often has an ethical dimension.

Ashley Hope Pérez: A life skill and a way of exploring the ethical implications of how and why and what we read. This subject of “difficulty” or discomfort in reading is an area of overlap between my fiction, which makes some people uncomfortable, and my academic work, which often examines how difficult topics are handled in literature. Some treatments of violence, for example, are horrifying but cathartic in a way that lets readers “move on” from the tragedy. Other treatments don’t give the reader that kind of release. It’s terribly uncomfortable to be put in that position as a reader, and yet I also think it’s important. It’s important because it shouldn’t always be easy to “read past” suffering. I’d even say that reckoning with discomfort often has an ethical dimension.

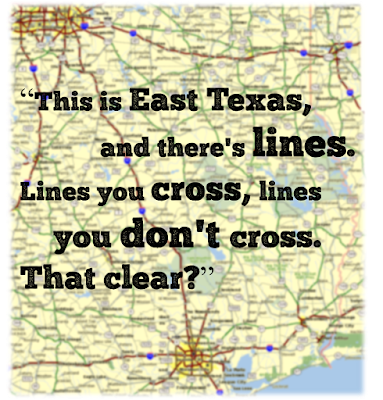

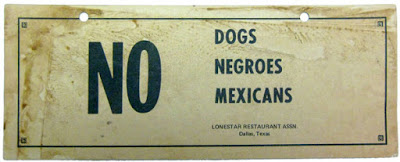

Tanita S. Davis: This kind of inescapable, you-can’t-shut-your-eyes-on-it discomfort – I love how Kirkus uses “unrelenting” in this context – this is something that I think a large part of our population (READ: me) would do anything to avoid, and yet I agree with Sarah — it tends to teach us a great deal to get out of our comfort zones. It’s like taking an Implicit Bias test and realizing that we’re frozen on a “right” answer — because it’s not right to us, not really. As hard as it is to learn – and it really does sometimes feel impossible, with the way we avoid, avoid, avoid any hint of “not nice” feelings – we have to pay attention to what our discomfort is telling us, as human beings, about our resistance, and about the ethics of bias and racism.

AHP: In the past ten years, I’ve seen students become increasingly receptive to this kind of work, especially around race, gender, and other forms of difference. The generation of students in my classroom now is still struggling with how to talk about these areas of life, but they get that they need talking about.

I think it helps to shift some of the focus from the “what” of the text (topics that make me uncomfortable, etc.) to the “who” of the reader. I often ask my students to register and then examine their reading responses. The sources of discomfort in reading can be hard to diagnose, but often when we really dig, we discover something about ourselves as well as the literature we’re reading.

At least that’s what I believe. And it’s an idea I encourage my students to try on.

TD: Yes. The idea of reframing a perspective as a new way into a story resonates with me. If I might bring up a book of mine, in a way, I did that with MARE’S WAR — we’ve all had WWII history ad nauseum, but telling that familiar piece of history from the POV of a person of color, a runaway, an underage, cynical little soldier whose future generations in the form of grandchildren were in every way her opposite (except in cynicism, in Talia’s case) – opened it up for ME to find a place in it, not to mention readers.

AHP: I find a lot of overlap between the ways of thinking and the practices that make writing possible for me on the one hand and the kinds of experiences or thought experiments that shift readers’ thinking on the author. Also, there’s such a difference between big-h history and all the smaller histories that are, fundamentally, about human experience rather than about big events.

SJS: Yes, I thought that was a really insightful comment about historical fiction, and the reason why readers always have the potential to learn something new even from fictional accounts of the same event or era.

SJS: Yes, I thought that was a really insightful comment about historical fiction, and the reason why readers always have the potential to learn something new even from fictional accounts of the same event or era.

TD: Jumping off of that, I wonder how writers can kind of take that advice, about reframing perspectives, and use it to delve into other works of historical fiction — more specifically, I wonder if that’s actually the key to working with fictional accounts of real things which happened entirely…?

I think of the incidents of racial violence in Charleston this summer and imagine how those events will be seen, seventy-eight years from now, the way we’re looking at the New London explosion – and I imagine how I would tell this story which is still so, so raw, and find a new way in, find a way to make it relevant and immediate to young readers seventy-eight years in the future who might have heard of it as simply another piece of history. Just as an exercise, how would you guys frame that history, if you were finding a way to tell it to young adults in the future? Is there anything which would cause us as writers – and readers and thinkers – to dig deeper, to see more, to care more, and thus extend those emotions to others? For myself, I think I’d be… I’d be a relative of the shooter, I think. That’s WELL outside my comfort zone – White, Southern, possibly public school educated to my years of private, religious education, possibly less involved in higher education — a working class person, living comfortably in a solid community, in a smaller, and in some ways more secure and insular world. How would something like that change me, as that extended family member? How would it change my belief in myself and in my place in the world?

SJS: I agree—a relative of the shooter, or a neighbor or former classmate, would be an interesting perspective from which to approach the story. To add to what you said above, I think I gravitate toward that perspective because it would be a means to increase my own understanding of how such a tragedy could occur, what would lead someone to do that, to feel that way, and to choose to ACT that way. I guess that’s the former psychology major in me, always trying to understand why people do what they do.

AHP: Or even the shooter himself. That would be the most radical—and uncomfortable—narrative space to enter for most of us. I found myself recoiling from the idea of narrating parts of Out of Darkness from the perspective of Naomi’s racist, abusive step-father, but I think I had to go there to capture the particular kind of horror that is part of her world. One of the best compliments my editor gave me about the book was that it was made more terribly by the fact that Henry (the stepfather) emerges as a deeply flawed human being rather than (just) a monster.

TD: Whoa. That’s an amazing compliment. When we see even our enemies in all their humanity, we’ve then truly achieved something in our understanding of the world – and in our ability to forgive. …all that being said, I definitely agree it would be a radical and uncomfortable narrative space, and take some major work to go there, and not punk out.

“…there is some good in the worst of us and some evil in the best of us. When we discover this, we are less prone to hate our enemies. When we look beneath the surface …we see within our enemy-neighbor a measure of goodness and know that the viciousness and evilness of his acts not quite representative of all that he is.” – Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., July 1963

Adorbs photo courtesy of the author.

Adorbs photo courtesy of the author.

Ashley Pérez is an enormously talented and intelligent human being as well as a brilliant writer, and we’re grateful she took the time – out of caring for her two little guys, the newest of whom arrived in June – and doing all of her other teaching and writing and family stuff to speak to us.

Stay tuned for the conclusion of this conversation on Monday!

What does it take to write and to edit a book like this? If you missed Ashley’s conversation with editor Andrew Karre back in May, pop over to Cynsations and give it a read.