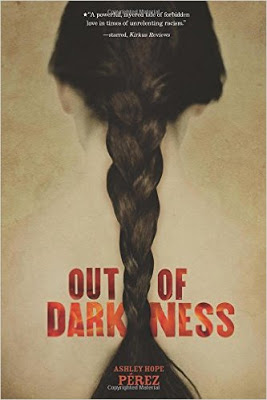

Welcome to Part 1 of our 3-part interview (we just couldn’t stop chatting!) with Ashley Hope Perez, author of the forthcoming YA historical novel Out of Darkness, which is based on real-life events (and which we reviewed here).

Not only was this a great opportunity to learn more about the story behind the story, it was also a chance to have a virtual conversation with one of our long-running blog buds and writer friends–because we DO like to put these in a less structured, more interactive form, going back and forth with the interviewee for more information and putting in a few thoughts of our own here and there. Check out the results today, tomorrow, and Monday! We were really pleased to delve into meaty topics like the difficulties of tackling such a tragic real-life event in fictional form and the challenges of writing about such events for teens (and teaching them).

With no further ado, here’s Ashley. 🙂

Sarah J. Stevenson: How did you get interested in this particular piece of 1937 history? How is it remembered in Texas?

Ashley Hope Perez: I grew up one county over from New London, so from a pretty young age I was at least vaguely aware of the disaster and the fact that many children had died. But until about 10 years ago, the explosion was almost never discussed. I think that silence was deeply painful for survivors and their families, and I’ve heard many stories of people who believed that they’d done something to cause the explosion (kicking a pipe, telling a lie) or were otherwise responsible for someone’s death. In the novel, two children change seats, and one of them dies. That’s the kind of situation that leaves the survivor wracked with guilt. “It should have been me…” That sort of thing did happen.

SJS: Was it was difficult to find first person narrative about the New London explosion? What kind of research did you do? Did you base your characters, however loosely, on historical individuals and to what extent? Did this story start with the characters, the setting, the premise, or…?

AHP: Most of the details related to the explosion are drawn from historical accounts. There are many oral histories and other records related to the disaster, and I was fortunate to access these at the London Museum and in the Stephen F. Austin University archives. About two years after I started writing the novel, an excellent non-fiction book came out on the explosion: Gone at 3:17: The Untold Story of the Worst School Disaster in American History by David M. Brown and Michael Wereschagin. From reading the book, I learned quite a few things I hadn’t uncovered on my own, like the fact that the Texas Rangers came out to guard the houses of school board members and that they actually turned away a mob of angry men. That detail becomes important in the novel, where I imagine what would have happened if the men had sought out another scapegoat, one whom no one was protecting.

For me, character almost always comes first. But then again, characters emerge in large part from the situations we place them in. I guess I could say that I almost start by writing somewhere in the middle of the story—a story whose arc I don’t even know yet.

Tanita Davis: I’m definitely a character person too – character and connections.

SJS: I can relate to both of those, as a writer—the story starting from a character, but also from a “what-if”. What if something different had happened? What if we followed the event from behind the scenes, or through the eyes of a different character? In a very fundamental way, character + what-if = STORY.

AHP: Absolutely. The “what if” about the Texas Rangers is actually secondary to another “what if”: What if a Mexican American girl from San Antonio found herself in rural East Texas? Where would she fit? What would her life be like? I think these kinds of questions are especially important when working with a historical topic. I can lose myself in research for weeks—almost a year for this book—but at some point a writer has to turn loose from the historical record and enter the world of fiction. That happened rather quickly since, at least in New London, minority voices simply weren’t a part of the account of the New London explosion. That exclusion went beyond this particular event; for example, when a “colored” school in the nearby town of Longview burned down, it wasn’t even covered in the local newspapers.

TD: Since you have a lot of background in education and are currently teaching at the Ohio State U, where would you see Out of Darkness fitting – in a history, sociology, poli-sci course? College, high school?

AHP: I’m interested in all thinking, feeling readers, but I write YA because I trust teens with even the most difficult stories. When I write, I often think of the students I taught during my three years in Houston. Whereas What Can’t Wait and The Knife and the Butterfly are about (very different) contemporary Latino experiences, Out of Darkness digs into aspects of history that I felt were still relevant to the lives of my diverse but mostly Mexican American students. I wanted to write a book that would make my students think and feel, not only about the past, but also about the present.

And I certainly hope Out of Darkness has a place on high school library shelves and in high school classes. Some brave HS teachers out there will recognize what it can offer to the study of literature and history (among other subjects).

TD: In that case, how would you see teaching this book?

AHP: I’d never dare teach one of my own novels, but if I were giving advice, I’d say that certainly the historical context needs attention. For example, the novel demands that we investigate the particulars of school segregation, which was three-fold in some Texas settings like San Antonio and Houston (white, black, and “Mexican” schools). There’s also the nature of migration and the patterns that can be detected in certain kinds of racialized violence (e.g., how violence is often triggered by external pressures on a community, such as economic stress or disaster).

But there’s a lot to think about, too, in terms of the actual experience of reading the novel. Although it has its moments of bliss, I’m aware that reading can feel very much like a descent into darkness, a descent that may not be especially welcome for all readers but that is, nevertheless, important. When I task my students with intense (they would say “depressing”) works in my university classes, I begin by building a framework for what it means to encounter difficult subjects in literature. We talk about the fact that, our responses to what we read require reflection, even interpretation. We ask questions like, “why am I uncomfortable/angry/frustrated with this portion of a text? What does that emotion do to my reading? To what extent is it a product of narrative and style? To what extent does it result from a mismatch between what the text is and what I wish for it to be?

Come back tomorrow–same bat channel–for Part 2 of our interview with Ashley!