Welcome to another session of Turning Pages!

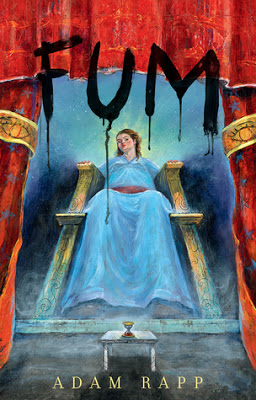

NB: This is not going to be the average review; I finished this novel despite my better judgment, hoping for some twist in the narrative that I wasn’t expecting, to make it work. I picked it up this book because of the title… and the fact that on the cover is a female. In fairytales, all the giants are male, and we have very few newer characterizations of tall girls in young adult literature, though the too-tall girl at the school dance was an ongoing trope for a lot of the earlier years of young adult lit. As this book was listed under fantasy, I thought it would be more of a fairytale. Last warning: It’s not.

Synopsis: After a pituitary tumor changes her body at age eleven, Corinthia Bledsoe emerges as 7’4″ and 287 pounds. She uses a special desk, and a special toilet, because she’s broken two. Her vision of a terrible triumvirate of tornadoes – and her subsequent loud, panicked warning of the entire school – is treated as some kind of violent dysfunction worthy of her being tackled by grown men, one of whom fantasizes as he does so about her bodily strength, and the kind of impact that she’d have on the gridiron. While Corinthia is already famous for her size and special-built desk, and for having a custom-built bathroom on campus, having broken two toilets since freshman year, she becomes terrifyingly infamous when the tornadoes come.

The story spins between Corintha’s increasingly disturbing relationship to the school and community to the tale of Billy Ball, who, struggling with gastrointestinal problems and reeling from the death of his father, is enacting unexplained racist cliché “red face” rituals and obsessing on Native Americans. Not fitting in at the same school, he comes up with a list of students and faculty with whom his path has crossed, and seems to be preparing himself for violence. He seems vaguely aware of Corinthia, but they only meet once, and it doesn’t propel the narrative in any direction. The third subplot returns to the Bledsoe household, and to a closer focus on Corintha’s mother, who believes herself to be somehow tragically martyred for being Corintha’s mother, and whose adult desires seem to be more important to her than her children’s struggles.

Despite being a junior, Corinthia doesn’t seem to have much of a view of the future, something which her ineffectual guidance counselor tries to elicit from her constantly, though her good-natured father seems prepared to accept whatever she’d like to do. Instead of a future, Corintha is mired in the present, as her brother disappears, and her mother goes into crisis. In possibly the oddest story thread in the entire book, Corinthia takes a road trip with one of the workmen fixing the school post-tornado, a man called Lavert. Corinthia’s friendship with him, a grown man with a criminal past, and her understanding of his mortality is definitely unexpected, and strains the credulity of the reader past bearing.

Observations: Grotesquerie is a 20th century literary convention which, according to Wikipedia, can be linked with sci-fi and horror. For me, this novel falls squarely under grotesquerie, simply because Adam Rapp seems to be thoroughly disgusted with everyone in the entire book, and in his disgust, renders them… disgusting. From the names of the characters and their ill-fitting, cacophonous names to the description of Corinthia herself beginning from page one – “woodsplitter’s hands,” and the “great caves of her nostrils.” Descriptions of her menstruation and nosebleeds, and comparisons between the two are a lovingly-depicted gross-fest.

Observations: Grotesquerie is a 20th century literary convention which, according to Wikipedia, can be linked with sci-fi and horror. For me, this novel falls squarely under grotesquerie, simply because Adam Rapp seems to be thoroughly disgusted with everyone in the entire book, and in his disgust, renders them… disgusting. From the names of the characters and their ill-fitting, cacophonous names to the description of Corinthia herself beginning from page one – “woodsplitter’s hands,” and the “great caves of her nostrils.” Descriptions of her menstruation and nosebleeds, and comparisons between the two are a lovingly-depicted gross-fest.

The narrative never takes off, as it is heavily weighted with an abundance of cloying description, producing a plodding plot in a claustrophobic storyline which draws in the unsuspecting reader with the idea of a real giantess and instead confronts them with body dysphoria juxtaposed with an awkwardness masquerading as intimacy. No one seems to grow or change; the bizarre incidents simply crowd together, threaded with domino-sized teeth and Together, this creates one of the most unkind and body-averse narratives I’ve ever read, and an alleged YA book which focuses less on the young adult, her challenges and changes than on her body, and the bodies of everyone around her.

The body-consciousness remains central to the novel. At 287 pounds, Corinthia is said to be pretty, but every other word out of the narrative disregards that, and paints her as disgusting and vile. She’s said to be third in her class – but every other description has her acting in bizarre and outlandish ways designed to repel the reader. Finally, Corinthia is alleged to have destroyed two toilets, once emerging covered in toilet water and swamping the girl’s restroom…which is …ludicrous, ignorant, and insulting.

FACT: People heavier than 287 use toilets on the daily. FACT: Nothing happens. Toilets – regular old public restroom toilets, and certainly the floor-mounted, vitreous china sort used in public schools – are rated to bear the weight of a THOUSAND vertical pounds, and yes, I am the big nerd who looked that up, but this jarring falsehood stands out. 287 pounds is just a number, and anyone who weighs that is just – still – a person. These scenes felt like a badly set-up, dehumanizing fat joke rather than a story detail filling in the blanks about who Corinthia is and what she’s about. Kids in high school are this weight on a regular basis, and stand to be hurt and insulted by this abhorrent characterization. Reader beware.

Corinthia – her family – her school – basically her entire corner of the State seems very white… yet the teens in the story are obsessed with people of color, to very significant degrees. Billy puts arrows in his hair and paints some racist cliche of warrior marks on his face. As her family dissolves, Corinthia begins to pal around with a grown man who is also a face-tatted, do-rag wearing cliché of a prison-release workman who, early in their relationship, refers to himself as “nigga”… For a novel which, up to that point, had displayed a casual lack of empathy for any of its characters, this white-guy-included racism wasn’t entirely surprising, but still reveals very poor taste.

Conclusion: I normally consider it a waste of time to review a novel which I vehemently dislike, but I made an exception for this because I walked into it unaware of its topic, or of any reputation with regard to its author. I won’t make the same mistake again. While some will assign this novel as an example of satire, or may find within it deep literary meaning, or even feel that it is merely misplaced in terms of audience, and would crossover well with adults, for me, there is too much left unexplained, and what may have been a brilliant venture does not pan out in its execution. My main thought is that it is disturbing, written with a specific distaste and aversion for the body, doesn’t have a discernible story arc, and is not especially respectful of the challenges and changes of adolescents, especially female adolescents. With its comparisons to people as animals and its basic disrespect for the teen body or mind, this novel seems to be an experiment with a broad scope which failed.

I received my copy of this book courtesy of the publisher. After March 20, you can find FUM by Adam Rapp at an online e-tailer, or at a real life, independent bookstore near you!